I commissioned this map of the world of AMOE a few years ago. It is now badly outdated and lacks detail. Artist credit – Renflower.

Disclaimer: I am not in any way posing as an authority on this matter. I do not have the credentials nor the experience to do so, this article is simply my opinion based on a personal love and enjoyment of the RPG genre. This is my approach towards constructing RPGs, as a novice gamedev and writer. So take everything with a grain of salt.

Agency – The Will

Purpose – The Mind

Does anything sound grander than a narrative-driven RPG? Simply saying the phrase brings to mind not only great RPG classics like Planescape: Torment, Baldur’s Gate, Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic (oh BioWare, you were truly giants among men), but also modern favorites like The Witcher 3 and Divinity Original Sin. Narrative-driven RPGs are TITANS. When you look at the content they offer, they are essentially the video game equivalent to Hollywood’s old sword-and-sandal epics. 400 voice actors! 500,000 lines of dialogue! 600-hour long story campaigns! Epic exaggerations!

And so on and so forth. These kind of RPGs are increasingly problematic for developers because they are intimidating. The amount of work that can go into even a smaller-scale narrative RPG is daunting, and often not worth the paltry returns. The genre isn’t dying (far from it, looking at the success of Larian’s wonderful Divinity Original Sin 2), but it also isn’t exactly tempting AAA studios either. Narrative RPGs seem to be currently relegated to AA developers and indies, and it’s often a passion project more than anything else. I’m generalizing here, but I can say with some degree of confidence that many devs working on RPGs do so because they love the genre, they have stories they want to tell and video games are their chosen medium for telling that story. I can certainly say that most gamdevs aren’t in it for the money.

RPG devs, if you’re in it to tell a story, to build an experience, make sure that it’s a good one. Everybody wants to be Chris Avellone, but nobody wants to put the years in that it takes to be a good writer. The necessity of great writers is woefully underestimated in the video game industry, and just about everywhere, really. Writers are professional storytellers, just as artists and programmers are professionals. We tend to forget that many types of games, RPGs especially, are a vehicle for the story, not the other way around. When you build a RPG, you should be remembered for the story, not only the mechanics of gameplay. Take a look at Baldur’s Gate and Planescape: Torment. As much as some people may like AD&D rules in game form, we can all agree that the industry has moved on. But the stories remain.

And that’s what I’m going to spend the rest of this long-winded blog post talking about. In my opinion, there are four, unavoidable pillars when it comes to writing a RPG:

- Lore – The Bones

- Characters – The Heart

- Agency – The Will

- Purpose – The Mind

Let’s dig in with lore, arguably both the easiest and hardest element to write for in a RPG.

Lore – The Bones of a Story

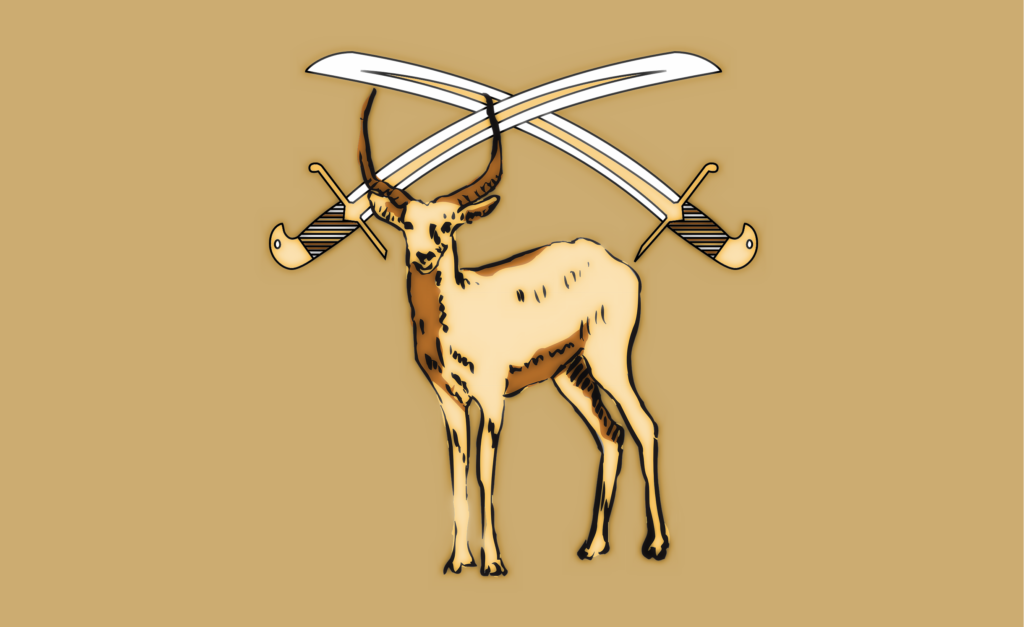

The flag of the Zimalayan Republic. After revolutionaries won the 8-year-long Zimalayan Civil War and ousted the royalist regime (which ended with the public execution of the entire royal family), a contest was held to decide the new state flag. A 15-year-old Corporal in the Liberation Army won with this design. What does that tell you about the current state of Zimalaya?

For this definition of lore, I’m conflating lore to all background knowledge and setting building. Lore is more than just snippets of text and a few lovely pictures, lore is a living world.

It’s easy to build a fantasy world. It’s hard to build a believable one. When I was younger, I spent countless hours dabbling with world building. It was great fun – and world building is at its core a childlike fantasy. My worlds were rich and colorful. It was easy to tell who the good guys were and who the bad guys were. I loved using grand terms like the “Alliance” and the “Darkness.” These were, of course, a product of my consumption of popular media. Looking back, I found that these worlds often fell flat because they lacked life. You see, I committed a cardinal sin in worldbuilding: I created a world for my characters, not the other way around.

At this point you might say, “Oh, well, you see I’m building a character-driven game, not a plot-driven one.” The difference between the two methods of storytelling being, of course, is that one is much more focused on characters than the plot.

But that doesn’t matter. Characters are ultimately a product of their environment. They are shaped and influenced by the world that they live in, and while many people opt to create a world around their characters, they lose a deeper, more realistic connection that happens when characters are born and molded in a world, rather than forming the world around them. One mirrors real life, while the other is the equivalent of a star child god being born, and most stories don’t revolve around star child gods.

In order to create a living, breathing world, it must exist beyond the characters that a player interacts with. I often use the Lord of the Ring series to illustrate this point because JRR Tolkien is a master lore builder. In my mind, he probably remains one of the best. The world of LoTR is not only massive geographically, but dense with history. There are vast tracts of lore that don’t impact the narrative of the main series in the least, but it exists because it happened. The history of the world doesn’t give a fig for Aragorn, Frodo, or the rest of the fellowship. Greater and more storied heroes have existed, have struggled against evil, and have either succeeded or failed. The lore of LoTR is filled with courage, tragedy and world-shaking events, and most of that isn’t even covered at all in the main series.

Now I’m not suggesting that RPG writers should go out of their way to write about events that have no impact on their story, but the point stands: years have come and gone, and the world will keeping spinning without your heroes (unless it literally doesn’t). Tolkien’s approach is to build his worlds first, characters second. This allows his lore to inform the construction of his characters – they are a product of the environment they are born into. A good practical exercise for those used to writing characters first is to list the principal elements of their world from the characters outward.

- Characters

- These are the dramatis personae that the player directly interacts with. Ultimately, they are the player’s greatest ties to the world. Who are they? What are their back stories? What are their current goals and motivations? What do they believe in? What tragic events and daring adventures have led to them being placed at the forefront of the player’s attention?

- Family and close companions

- Family is one of the single most important influences on a person, so why does it seem like RPGs are filled with nothing but heroic orphans? Even orphans have loved ones, people who shaped their lives and taught them right from wrong (or wrong from right). In reality, much of our own goals, fears and regrets are formed from our interactions with family, childhood mentors and lifelong friends. The same is true for your characters as well. Look at the Baldur’s Gate series: many of the character-related quests deal with your party members coming to terms with their family. Whether it be taking a dark path to avenge a murdered sister, or escaping your family and society’s expectations of you to wed someone of comparable wealth, characters are inevitably drawn back to their own baggage – which for many is an apt metaphor for family.

- Regional powers, factions, organizations and municipalities

- Nations and empires are not homogenous amalgamations from coast to coast. Especially in fantasy or historic settings, there’s bound to be a lot of regional flavor, and it would be a missed opportunity to present every town or city as a copypasted Generic Imperial City. What are the local powers in this region? What factions are vying for control, and what are the histories of these factions? Are they simply the local chapters of a galaxy-spanning peace-keeping force, or are they their own, singular entity? Small factions have a place and writers would do well to remember this.

- Nations or national factions

- These are now larger, more powerful entities with more detailed histories. Nations and corporations, or very powerful criminal organizations, occupy this tier. They will have their own unique cultures, worship weird and interesting gods, and have their own ethics and beliefs. Culture is… important. And they can be hard to create, which is why many of us steal from real life.

- Nations have long memories and may bear grudges against their rivals, or feelings of friendship towards historical allies. There likely exists a complicated web of alliances and animosity, and this is great opportunity to flesh out your world.

- Global powers

- Here are the great powers of the world, the empires and MegaCorps and theocratic despots. In a fantasy setting, these will be the entities that lead the armies of good and evil (or the armies of okay and not so bad). In a Sci-fi setting, they may be apathetic and uncaring, either too large and burdened by bureaucratic busy work to be effective, or had already risen to a higher plane of existence and can’t give a fig for us mortals. Nonetheless, the existence of these powers WILL affect your characters. The actions of these powers WILL move the plot. Unless the scope of the story is very narrow, it can be all too easy for these powers to overtake the narrative.

- Cosmic powers

- Gods, all-powerful aliens, people who won the superhero lottery. These entities don’t always play a large role in RPG narratives, but they do sometimes show up. Gods may be more powerful than nations and global powers, but they are inherently individuals. Which means they have flaws: jealousy, hubris, wrath, lust, etc. They can also have long histories, which means that for most immortals, they have a long list of friends and an even longer list of enemies.

My method is easy. Take out a sheet of paper (or open a new document, whatever you swing with), and simply list a few details under each of these categories. And as game development/writing advances, add more details every day. Soon, you’ll have enough that you can consistently draw out your notes into something bigger.

A good example of modern lore building leading to fleshed out characters is The Bloody Baron from Witcher 3. The arc follows Phillip Strenger, a former soldier and now self-proclaimed baron ruling from Crow’s Perch in Velen. The Bloody Baron quests were a fan favorite of players, but as a gamedev and writer, it should blow you away at what the Witcher 3 team did: layers and layers of lore.

Let’s quickly break it down via the above method.

- Character: Phillip Strenger

- Family and close companions: His wife Anna and daughter Tamara, as well as his band of former soldiers

- Regional connections: Strenger is the regional power in Velen.

- National connections: scattered and destroyed Temerian forces nearby, but the country as a whole has largely ceased to exist. Redania’s army is at the border.

- Global connections: Strenger’s dealings with the Nilfgaardian Empire, which is poised to absorb the region by right of conquest.

- Cosmic connections: By a strange twist of fate, Strenger was brought into the path of Cirilla Fiona Elen Riannon, playing a small (if somewhat vital) part in her destiny and the ultimate resolution of Ithlinne’s Prophecy.

Spoilers from Witcher 3 below:

We typically think of lore as the great deeds of ancient heroes or past events from long ago. That’s part of it, but I like to think of lore as layers. Layers that you can peel back from the veneer of a game and expose the hidden architecture. In many games (or any media really), you peel the layers back and you find nothing holding up the world. It’s empty and artificial because that’s exactly what it is, an artificial world that does not exist outside of the current narrative. However, if you peel back the layers and you find that there are even more layers to explore, then you increase the user’s immersion.

With the Bloody Baron, your first impression of the man is that he is nothing but a cutthroat leading a bunch of cutthroats to take advantage of a power vacuum. That’s true, and that’s ultimately what Strenger is: a war profiteer. But then the player is drawn into his quest line. They are tasked with finding Strenger’s wife and daughter. As Geralt travels across the barren countryside, dodging monsters and bisecting bandits, he not only learns more about Strenger’s motivations, but also about the family’s past, Strenger’s precarious alliance with Nilfgaard, and the history of Velen. Strenger and his family (and their eventual fates) are a personal story, but more than that, they really embody all of war-torn Velen. Everything from Strenger’s career as a soldier to his wife’s pact with the crones, and even his daughter’s eventual enlistment with the magic-hating witch hunters… everything both supports and is supported by lore.

The Strenger family isn’t some independent entity, they are something created by the world around them: Phillip and Anna would’ve never met if he hadn’t taken a spear to the shoulder in the battle of Anchor, when he fought under Temeria’s banner. His time away from home turned him into a hard man, quick to reach for drink and the caresses of other women. Anna, embittered by her absentee husband, took a lover, who Phillip then murdered. This in turn, causes all of their eventual strife when the player meets them.

Years later, with the armies of Temeria shattered by the Nilfgaardian advance, Phillip decided to take his chances and lead his small ragtag, broken army to Crow’s Perch, where he set himself up as a warlord, but in truth nothing more than a bandit chief leading murderers, thieves and rapists. Strenger is solidly connected to the history of the land, and it is impossible to remove him to a different setting without losing much of his history. Move him anywhere else, and he ceases to be Phillip Strenger, former soldier, failed despot, husband to a resentful wife, father to a estranged daughter. All the tragedies and misfortunes that affect Strenger ring all the more true because of everything that led him to this path… all the pieces were there long before the player even came onto the scene.

That’s the power of great lore.

Want to learn more about what I’m building? You can read my development schedule here.

Comments are closed